The Journey of a Japanese as a Second Language Researcher

In my master's, I conducted an experiment on audiovisual speech perception of multilingual learners in Japan. I want to share what I learned and how it shapes my future research plans.

Dear Katarina Woodman,

Congratulations! We are pleased to share that your article "Audiovisual Speech Perception of Multilingual Learners of Japanese" has been accepted for publication in International Journal of Multilingualism.

After two years of in-depth studying and working hard to complete my master’s degree, my first article as the primary author felt like I had passed through the threshold of becoming a real researcher. However, perhaps that’s my imposter syndrome still lingering.

With the publishing of this article, I decided to meditate on the path my research has wandered down. After all, my goals at 18 when I graduated high school and thought I’d become a neurosurgeon have clearly changed over time.

In this article, I would like to discuss this journey, explain where this study came from, and what it means for my future research as a doctoral student.

A Baby Researcher

As an undergraduate student, I began taking a keen interest in participating in research. First, I joined a neuroscience lab conducting microglial studies on Alzheimer’s mouse models. Later, I joined a perceptual psychology lab that looked at peri-body space in various contexts.

This was when I first began to study cognitive sciences, which slowly became a growing interest, peaking when I attended the Association of Scientific Studies of Consciousness (ASSC) conference held at Western University in London, Ontario. At this point, I enjoyed combining ideas I had studied in my philosophy of mind classes with what I learned in my psychology classes, ultimately leading to my switch from the pre-medicine track to the research track.

At this time, I didn’t know what I wanted to research; I just knew that I loved being in the labs and had so many questions I wanted to answer. While I gained a lot of different skills, perhaps one of the most influential experiences at this time was a research project where we went through historical psychological studies on psychedelics published between 1890-1968 (when psychedelics were outlawed in the United States).

At the same time, my passion for languages simultaneously grew as I studied abroad in 2019/2020 at Nara University of Education (NUE) and continued investing large portions of my time in learning Japanese. Suddenly, I had two halves: a language learner and a psychological researcher.

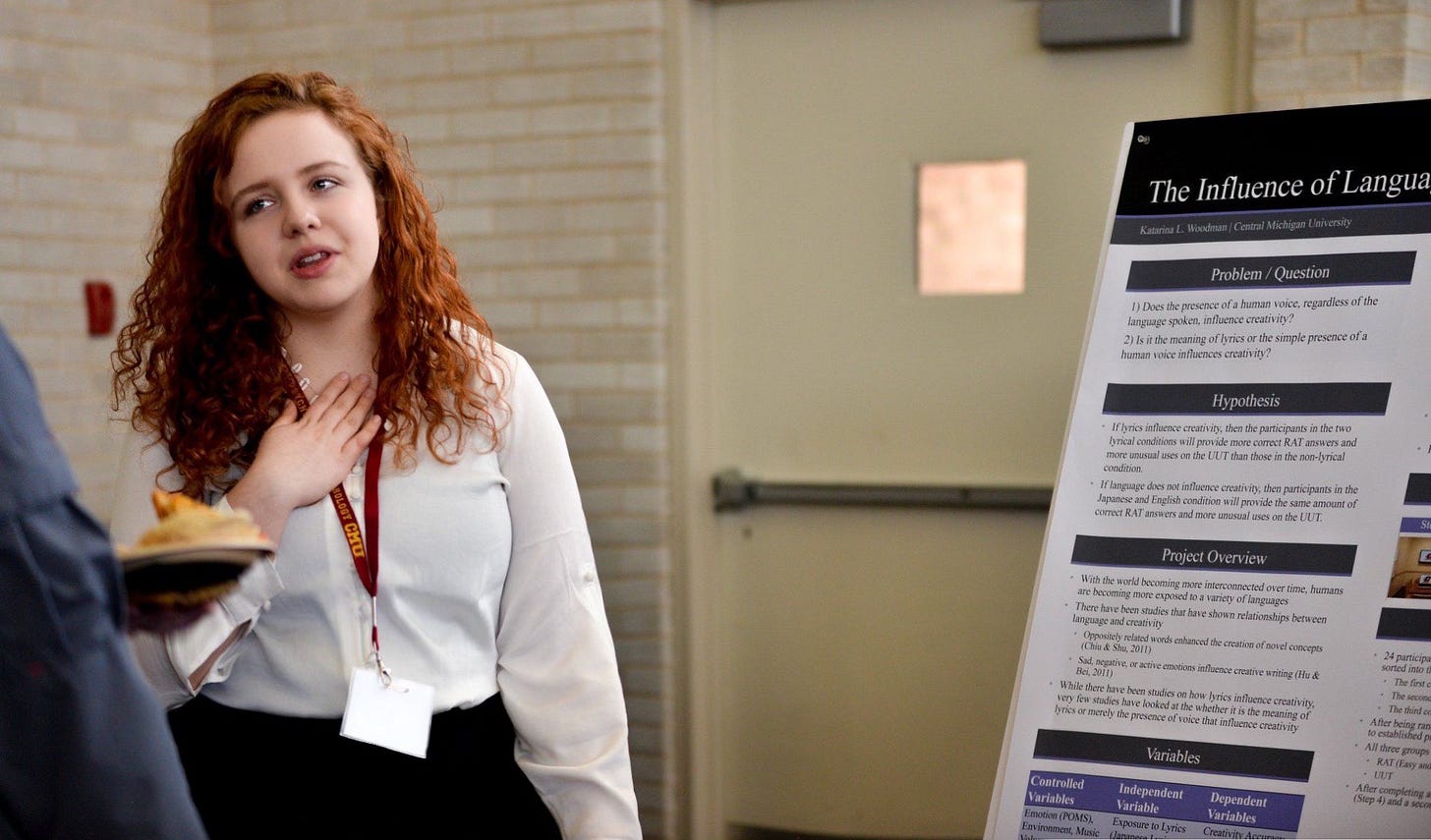

This influenced my senior thesis as we were presented with measures of creativity and asked to design an experiment. I designed a study on the influence of language exposure on creativity.

However, while I had intended to graduate shortly after my time at NUE and immediately enter Kyoto University, life circumstances changed, and a pandemic closed the borders back to Japan.

And so, I decided to spend a year to complete a degree in philosophy, finding a passion in Buddhist and Hindu texts, which resulted in a second senior thesis on the construction of a conventional self and the anatta (or no-self) doctrine.

Upon graduation, I had these three fields I loved: languages/linguistics, cognitive psychology, and philosophy of the mind. While passionately reading about these topics, I was ready to move on to graduate school. However, Japan’s borders were still closed to non-Japanese citizens due to the pandemic.

I couldn’t move into my apartment in Kyoto, which forced me to abandon the contract completely. Instead, I had to attend online classes at night due to the time zone differences between Japan and America, and I worked as a barista at Starbucks during the day. As I worked in the service industry during the pandemic, I couldn’t help but begin to notice an interesting difference I was observing between Japan and America:

Masks

While living in Japan leading up to the pandemic, I had grown accustomed to always wearing masks. It was common for classmates to wear masks to classes for no reason other than feeling like it. When the pandemic started, masking culture was already a norm in Japan, making masking fairly easy to implement.

On the flip side, America was not having an easy time with masking. While it was common to see masked classmates in Japan even well before the pandemic, suddenly, Americans were constantly fighting over whether they should or shouldn’t have masks.

However, what piqued my interest in all of this was a common complaint that it was hard to understand one another when wearing a mask—a problem I never noticed or heard about in my entire time living in Japan.

So, this difference I observed between Japan and America sparked my curiosity and led me down a rabbit hole of audiovisual speech perception.

We’re All Lipreaders

Lipreading is using lip movement as a visual cue to understand speech. Many people quickly associate lipreading with the deaf community because it’s common for deaf individuals to rely on lipreading as a part of their communication, especially when sign language is not an option.

However, many nonverbal factors contribute to communication in all languages, whether signed or spoken. These include facial expressions, body language, context clues, and lip movements.

When considering how language is processed, it’s easier to think of the brain as a predicting machine. The brain is constantly trying to guess what is about to happen around it, using a variety of cues from your environment and experience to either validate or reject the predictions it forms.

The shapes the mouth makes when pronouncing certain phonetics are part of this process. This visual information gets combined with the stuff you actually hear, which is called audiovisual integration.

Within gaze perception research, this audiovisual integration is often a part of visual attention, resulting in certain changes in how the eye moves during communication. Essentially, when engaging in conversation, our gaze naturally shifts between the speaker's face and other relevant visual cues, which researchers can measure with eye-tracking devices.

An example of this can be seen in a study by Hisanaga, Sekiyama, Igasaki, and Murayama. They investigated how cultural and linguistic factors influence speech perception by examining how people combine what they see and hear. The comparison between Japanese and English speakers was based on three key measures: response time, brain activity (measured with EEG), and eye-tracking.

This study found that English speakers benefited from seeing mouth movements, speeding up their response and reducing cognitive load. Essentially, integrating auditory and visual speech cues supports this gaze behavior by providing complementary information, making listening much easier.

As I continued reading through this literature, I realized that this could be one of the reasons why many people might have been saying they struggled to understand others while wearing masks. If you grow up using visual cues like lip movement as part of your communication process, it makes sense you may not be used to communication without it when it’s removed.

However, the question remained. Why was this seemingly not a problem that Japanese people often spoke about?

Japanese vs. English

Going back to the study we discussed before, while English speakers processed speech faster with added visual cues, Japanese speakers were instead slower in the audiovisual condition compared to the auditory-only condition.

The ERP results showed that visual information also influenced early brain responses for both English and Japanese speakers. However, for English speakers, this influence continued into a later brain response, suggesting that English speakers rely more on visual information when perceiving speech.

In an article written by Professor Sekiyama, she presented various evidence from recent studies showing differences in how English and Japanese speakers use visual cues.

Developmental data showed that visual influence increased with age for English-speaking children, but this change did not occur for Japanese children.

Using eye-tracking data, she found a gaze bias toward the mouth in English speakers, which did not exist in Japanese speakers.

In event-related potentials (ERPs), she demonstrated that listening to multisensory speech was more efficient than auditory-only speech for English speakers, while the opposite was true for Japanese speakers.

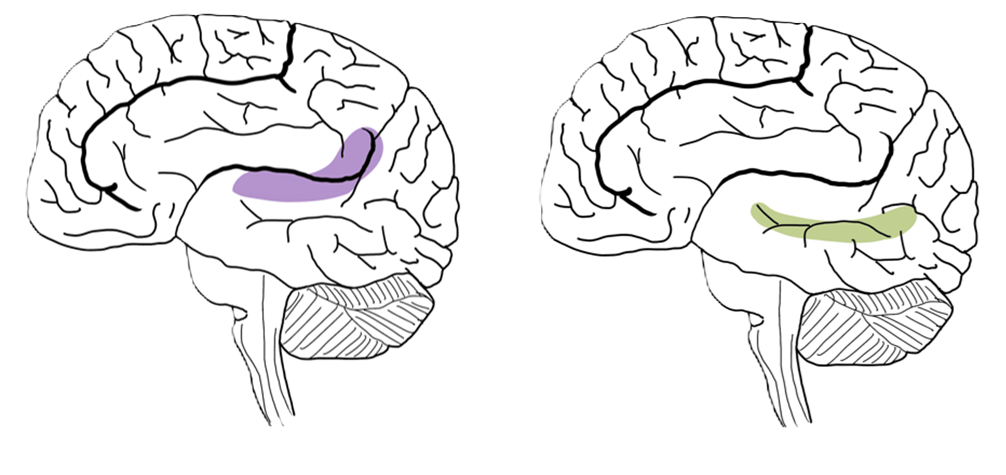

Even in fMRI studies, she found neural connections (or communication pathways) occurred in English speakers' primary auditory cortex (A1). For Japanese speakers, these connections happen in the superior temporal sulcus (STS), typically the site for the multisensory integration of speech.

This suggests that, unlike Japanese speakers, the auditory cortex is the focal point for receiving, processing, and transmitting visual information to and from other brain regions in English speakers, occurring much earlier in the listening process.

Now, you might be asking yourself why this might be the case.

There are two possible reasons for this: 1. differences in the languages themselves and 2. differences in the cultures the speakers come from (or likely some blend of both).

The language explanation poses that the difference comes from how the languages are phonetically distinct. Japanese has fewer phonetic components than English, making lipreading less informative in Japanese conversations. For example, Japanese is divided into only three groups of consonant clusters, compared to the 46 consonant clusters in English. This means that far fewer mouth shapes are formed when speaking Japanese, providing much less lipreading information.

As a result, the average Japanese speaker has less to gain from lipreading compared to English speakers. Unlike English speakers, because lipreading becomes less informative, Japanese speakers may rely less on mouth cues for overall speech comprehension.

The cultural explanation for the differences between Japanese and English speakers in audiovisual speech perception relates to cultural differences in attention. Specifically, it is proposed that Eastern (Japanese) and Western (English) individuals have different visual attention patterns when processing speech.

Western cultures tend to focus more on the mouth, facilitating lipreading and the integration of audiovisual information in speech. In contrast, Eastern cultures, including Japan, use other context clues for communication (being a high-context culture). This means they are more likely to prioritize the eyes or other facial cues, reducing the reliance on visual speech cues like mouth movements.

Where it Gets Complicated

It’s clear that language background can heavily change your gaze perception, but the debate of how much of this comes from language and how much comes from culture is complicated. Especially when you start looking at multilinguals.

For example, another study by Professor Sekiyama compares Chinese and Japanese speakers with a measurement called the McGurk effect.

Essentially, the McGurk effect is a phenomenon in which conflicting auditory and visual information during speech perception leads to the perception of a different sound, blending both cues. For example, hearing the sound "ba" while seeing lip movements for "ga" may cause someone to perceive the sound "da."

Both Chinese and Japanese participants had a weaker McGurk effect compared to English speakers, which helps validate the cultural argument. However, one important detail is that Chinese participants, particularly those who have lived in Japan longer or have had more exposure to their second language (Japanese), are more susceptible to the McGurk effect.

Another study by Professor Viorica Marian examined how bilingualism affects auditory and visual information integration, focusing on the McGurk effect in Korean-English bilinguals. The study found that regardless of proficiency, bilinguals experienced the McGurk effect more often than monolinguals. Although gaze bias measurements were not used, the researchers discovered that Korean-English bilinguals relied more on visual information when processing speech.

What’s interesting about this is that it suggests that acquiring a second language may enhance their use of visual cues, such as lipreading, in speech perception.

Of course, cultural differences can still play a role in both cases. For example, less direct eye contact in formal Japanese communication may affect the Japanese participants' reduced reliance on visual cues. However, cultural differences between Western and Eastern cultures are not the sole explanation as can be seen in the bilinguals.

Returning to our explanation of language, we see another possible factor. When you think of a bilingual as a language user with an integrated language system of two languages, you can see a similar situation to the differences between English and Japanese: bilinguals have more complex phonetic dictionaries than monolinguals.

Think of it this way: we all have a "dictionary" in our heads. Part of this dictionary includes the different phonetics of our language, such as how they’re written, what they sound like, and how we form them in our mouths. The size of this dictionary, especially the part that deals with pronunciation, impacts how we integrate audiovisual information.

For bilinguals, their dictionary combines phonetics from both languages they speak, making their "phonetic dictionary" larger than that of monolinguals. Because of this, lipreading becomes a more useful strategy for bilinguals when listening to language. The visual cues help them interpret the distinctions between the wider variety of phonetics in their dictionary, especially when using their second language.

My Master’s Project

I had been working on my literature review as a research student at Kyoto University (mostly because I couldn’t enter the country to take my entrance exam).

When the next entrance exam testing period came, my university made an unprecedented decision and allowed me to take the entrance exam online, which meant I had an oral exam from 10:00 pm to midnight with no breaks. As someone with a major speech impediment and who’d been sleep-deprived running purely on discounted Starbucks coffee, this created a unique set of anxiety.

Yet somehow, I managed to pass.

Luckily, by the time the entrance ceremonies began, the borders finally reopened, and I arrived in Japan, ready to hit the ground running as a master’s student—mostly. The long flights and time difference caused me to miss most of the orientation, and I was scrambling to improve my Japanese skills to keep up with all the difficult lectures.

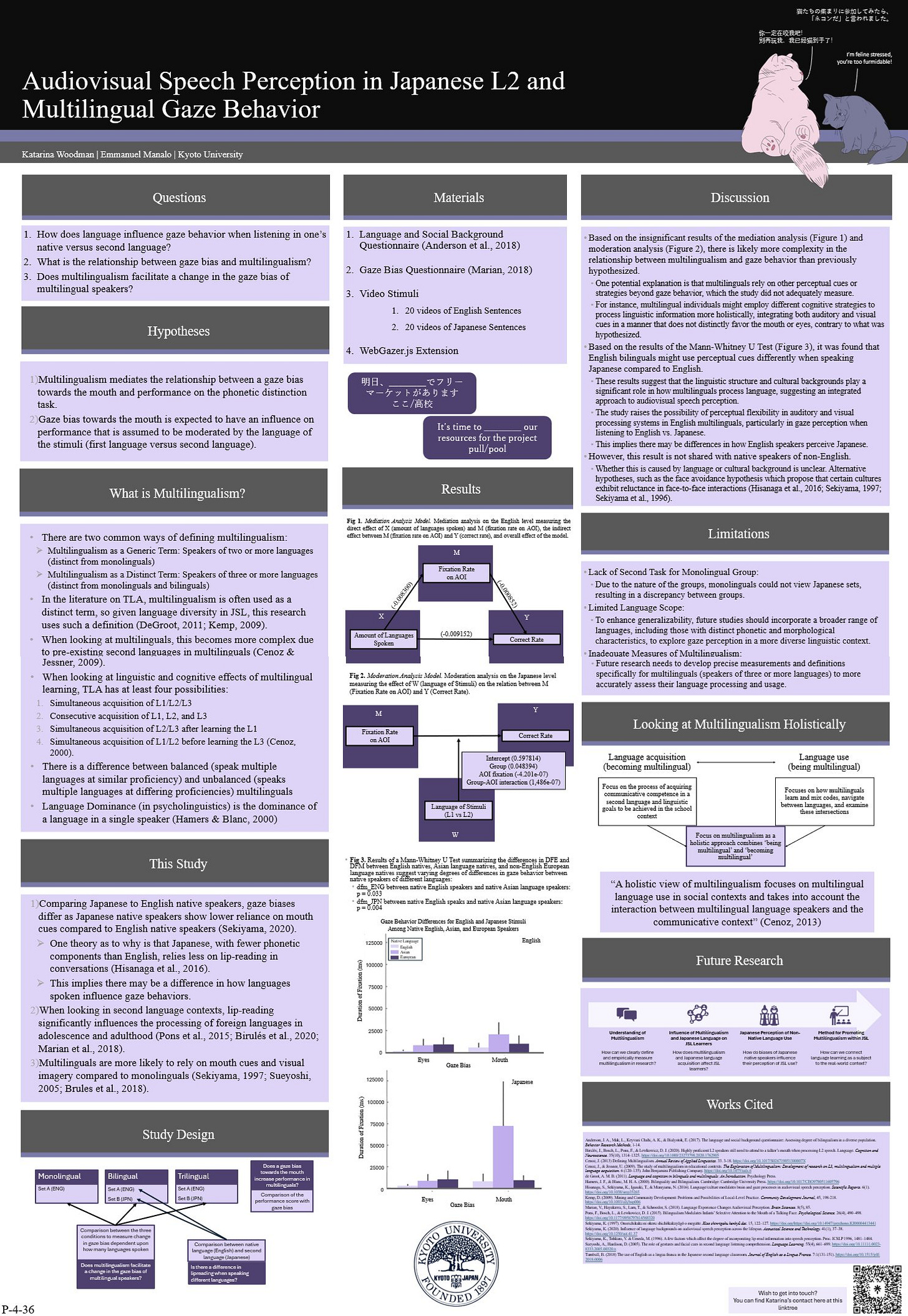

Aside from coursework, the biggest thing I had to do as a master’s student was a research project. Without one, I would not be able to graduate. After my time doing literature reviews as a research student, I was left with a few questions.

Many studies I looked at focused on gaze behavior, either in the participant’s second language or using tasks like the McGurk effect, which aren’t necessarily bound to a single language. This left me wondering what the impact of speaking in a second language had on these bilinguals compared to speaking in their first language.

Additionally, while previous research has shown the relationship between bilingualism, gaze perception, and language background, there are still many gaps in our understanding of these connections. For instance, most studies have focused on comparing bilinguals and monolinguals, with little exploration of how more complexities in multilingualism, like trilinguals, might differ.

This raised an important question: Does the gaze behavior of multilingual individuals differ from that of monolinguals or bilinguals?

Understanding these differences is important because it can provide insights into how learning multiple languages affects cognitive processes and perception strategies.

From this, I had two research questions:

Does multilingualism facilitate a change in the gaze bias of multilingual speakers?

Is there a difference in gaze bias when listening to different languages?

In order to answer these questions, I designed an experiment around two hypotheses:

Multilingualism and bilingualism mediate the relationship between a gaze bias towards the mouth and performance on the phonetic distinction task.

Gaze bias towards the mouth influences performance that is assumed to be moderated by the language of the stimuli (L1 versus L2).

For this study, we defined bilingualism as speakers of two languages and multilingualism as speakers of three or more languages. We used this definition because we were interested in understanding the possible influence of third language acquisition, as many Japanese language learners are from countries that speak both English and a different native language, making Japanese not the second language they acquire.

At first, we considered using the same McGurk effect that previous studies often relied on, but we realized that it wouldn’t be possible to compare how the participants' gaze behavior changed when listening to their native language versus their second language. So, instead, a novel task was created.

This involved two sets of videos in English and Japanese. We identified difficult phonetics to distinguish and selected a set of minimal pairs where each word only differed based on one phonetic component. The minimal pairs are seen in the table below:

Then, in each video, the speaker would say a sentence and one of the words from the minimal pairs would be spoken within the sentence. The participants would then report which word they heard. Some examples are shown below:

The participants saw these videos in a randomized order in two blocks (which were counterbalanced to avoid what is known as the order effect). Their performance was calculated by how accurately they responded based on what they heard in each video.

Along with this task, the participants also underwent eye-tracking using their computer’s webcam. Initially, we intended to use an eye tracker within our lab. However, recruiting participants was difficult when the borders were still closed to most foreigners, and social distancing was strong. So, we switched to an online method already validated across multiple labs in the “ManyBabies Project.” Then, it became a push to find 54 participants.

What Did We Find?

Contrary to our initial expectations, the results didn’t show significant evidence that gaze behavior mediated the relationship between the number of languages spoken and performance on the task. While the hypothesis predicted that multilingual and bilingual participants would fixate more on the mouth area than monolingual participants, the data did not support this.

There are many reasons why the initial hypothesis may not have been found in the data. For one, the multilingual group consisted of a diverse set of individuals who spoke languages from all over the world.

For example, we had Malaysians who spoke Malay or Mandarin as a household language, English as a community language, and Japanese now that they lived in Japan. We also had mixed participants who spoke languages like French as well as Japanese in their household growing up or individuals who had immigrated multiple times as kids, living in countries like Saudi Arabia, China, or the US before moving to Japan.

So, it’s clear that when analyzing all of the data together, this diversity of background could bring in confounding factors.

Another reason may be that the relationship between multilingualism and audiovisual speech perception is more complex than initially hypothesized, making the model we used inadequate to fit the data we had.

For this reason, we chose to do some post-hoc analysis to investigate this topic further. This type of analysis is a statistical test a researcher conducts after an initial study to explore unexpected findings or investigate additional questions that were not part of the original hypothesis.

One thing to remember is that post hoc analyses help identify patterns or differences that might have been overlooked in the main analysis. However, we need to approach post-hoc results cautiously because they are often data-driven and not based on prior hypotheses, which increases the risk of finding patterns due to chance. So, the findings should be interpreted as exploratory rather than conclusive unless confirmed by further research.

In the post-hoc analysis, we found that native English speakers, specifically those who were bilingual or multilingual, differed in their gaze patterns based on the language of the stimuli (English vs. Japanese).

This was particularly evident in the way bilingual/multilingual native English speakers shifted their gaze between the eyes and mouth more when exposed to English stimuli compared to Japanese stimuli. This difference suggests that English speakers may rely more on mouth cues when interacting with English than Japanese.

Conducting a test known as the Mann-Whitney U Test, we found differences in gaze behavior between native and non-native English speakers when exposed to both English and Japanese stimuli.

Non-native English speakers, particularly those from Asian language backgrounds, relied more heavily on visual cues from the mouth when processing Japanese. Which was found to be a significant result in the Mann-Whitney U Test, but can also be seen in the graph below.

So, how can we interpret this post hoc analysis?

While we cannot draw strong conclusions in this case, there are clearly some distinct trends among native English speakers. Specifically, English speakers seem to adjust their visual attention strategies based on the language they are processing.

What Comes Next?

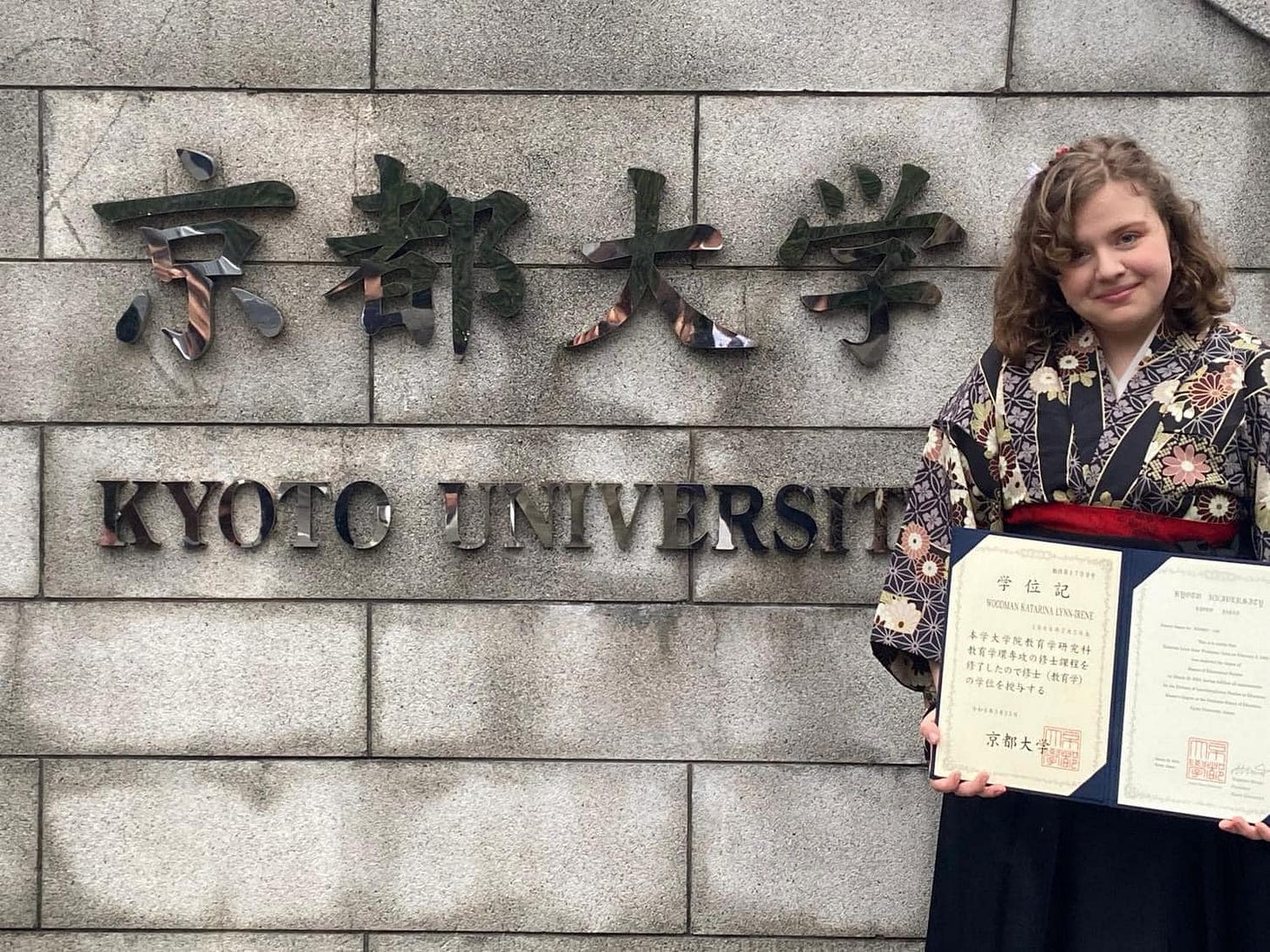

This study comprised most of my Master’s research, allowing me to graduate in April 2024.

Initially, it was described in depth in a 48-page dissertation titled “Audiovisual Speech Perception in Second Language Listening submitted in 2023 and now stored within Kyoto University records. Then, post-graduation, it was reduced to the now-published article titled “Audiovisual Speech Perception of Multilingual Learners of Japanese” in the International Journal of Multilingualism, which you can reference if you want a more thorough explanation of the methods, results, and discussions.

One key question remaining at the end of this study is understanding how the Japanese language affects second-language speakers. We can see quickly that the model of who a Japanese learner is quickly gets complicated trying to understand the diversity of backgrounds Japanese learners come from, both culturally and linguistically. Yet it is clear that cognitive strategies and ways of processing language change when learning Japanese and (likely) switching between English and Japanese.

With these changes, the major debate between cultural and linguistic influences remains. In some ways, when a learner comes to Japan and learns Japanese, they aren’t exposed just to linguistic information but also to Japanese culture.

In debates around multilingualism, when we discuss it from a holistic perspective, we find a major distinction between “language acquisition” and “language use.” This was well pointed out in the works of Professor Cenoz.

Language acquisition is the process of becoming multilingual, meaning it includes elements like scaffolding for language learning, using elements from other known languages as resources, attending courses, and so on.

Language use, on the other hand, is instead about being multilingual. It includes things like identities within the language, translanguaging, and how non-native speakers naturally use communication outside of the classroom setting.

Much of the literature on Japanese language education largely focuses on the language acquisition side of multilingualism. This means many studies focus on the learning process of Japanese, such as what helps students acquire the language and teaching methods for educators.

While research on language acquisition is important, it is equally important to have a holistic understanding of who a non-native Japanese speaker is, including how they naturally use the Japanese language.

For this reason, my research goal is to address the language use side of Japanese language education in a project titled “Holistic Perspective of JSL Learners as Multilinguals.”

To do this, it’s important to understand both the cognitive influence of the Japanese language on Japanese learners and the social influence of actually living in Japan and interacting with Japanese native speakers.

The ultimate goal is to have an in-depth understanding of Japanese language education on an individual and social level so that we can navigate this journey of learning Japanese.

Woodman, K., & Manalo, E. (2024). Audiovisual speech perception of multilingual learners of Japanese. International Journal of Multilingualism, 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/14790718.2024.2402330